In the previous iterations of Shrine to Sea’s Celebrating Local Stories series, we have explored the colonial history behind South Melbourne, Albert Park and surrounding land following colonisation. However, central to this area is the ancient connections for the Traditional Owners of the Kulin nation, who occupied this country for tens of thousands of years. The form of the land has been shaped by Traditional Owner life and activity but was later invaded by British settlers – leaving lasting, devastating effects on the Traditional Owners. The history of the Traditional Owners’ connection, use and care of Country, as well as the traumatic impacts of colonisation, will be explored in this final instalment of the series.

Before the arrival of British colonists, the place we now know as Melbourne was the Country of the Woi-wurrung (Wurundjeri) and Boonwurrung (Bunurong/Boonwurrung) language groups, which are two of the five tribes of the Kulin nation. Port Phillip was originally known as Nerrm.

The natural features of Nerrm represent an ancient landscape. The Shrine to Sea boulevard area and its immediate environs encompass an area that stretches from the high ground of the Domain, which formed a bank of the Yarra River (Birrarung) through to the coastal edge at what is now Middle Park and Albert Park, which was mostly low-lying and prone to flooding.

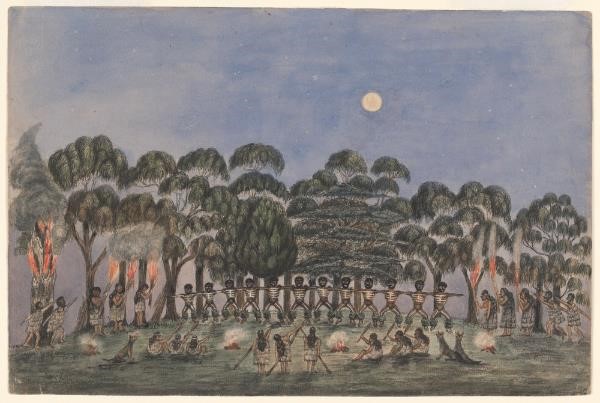

A corroboree on Emerald Hill in 1840 by Wilbraham Liardet, 1875, based on an earlier sketch he had made in the 1840s. (Source: State Library Victoria)

For many thousands of years, Traditional Owners managed the landscape in sometimes subtle but critical ways to maintain necessary resources for human survival.

They carried out seasonal burns of Country to regenerate plant life and stimulate regrowth, which managed the fuel load and helped avert bushfire and also sustained hunting grounds for grazing animals like kangaroos.

They built fish traps at the edge of lakes and lagoons, and harvested plants such as the tuber Murnong or Yam Daisy (Microseris spp.) which was a mainstay of their diet.

They formed middens along the coast where shellfish were harvested and consumed over many thousands of years.

However, the experiences of Traditional Owners people and the transformation of Country were dramatically impacted by colonisation. Despite the Kulin nation occupying Nerrm for tens of thousands of years, the Traditional Owner history of the area is less documented and less understood than our colonisation history.

For this reason, the following is not a complete picture of the Traditional Owner history of the Shrine to Sea boulevard area, but rather a gathering of insights to tell an important story.

Shaped by the sea

Nerrm (Port Phillip Bay), once described by one Elder as having been a vast “kangaroo hunting ground”, has been strongly shaped by the ocean and the impact of sea level changes over millennia.

Around 20,000 years ago, the sea level was much lower, so more land was exposed on the coastal edge of southern Australia, including the Bassian Shelf that formed a land bridge to Tasmania.

The low-lying area was a natural basin and formed a grassy plain, with areas of wetlands at different times at its lower points.

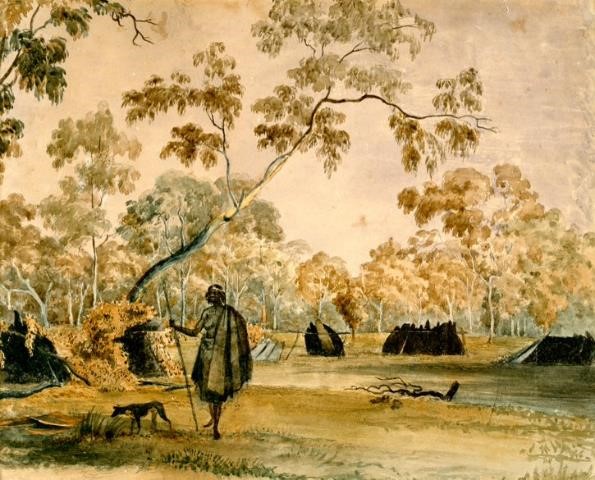

An Aboriginal camp on the south bank of the Yarra, sketched by John Cotton, c1845. (Source: State Library Victoria)

At the end of the last Ice Age, the ice caps melted, and the sea level rose significantly. The land that became Nerrm was inundated. The flooding occurred slowly over thousands of years, reaching a high point that covered much of the coastal areas of Melbourne, and then subsided, forming the present coastline between approximately 5,000 and 6,000 years ago.

The area was formed when the sea level fell, and the waters retreated to the coastline in its current form.

Boundless resources

Prior to the arrival of British settlers to the area and the changes that brought, the landscape would have comprised the outlying ridges land system.

Vegetation was varied, and included grassy woodland species, riparian woodland species, grassland species and brackish wetland species.

The extensive lagoon area (now Albert Park Lake) and another smaller lagoon between Albert Park Lake and the foreshore were part of the broad delta of the Yarra River (Birrarung). This was much wider in past millennia, with the Sandridge Lagoon believed to have been a former outflow of the Yarra River.

The area was rich in resources, including birds, fish and other freshwater and saltwater animals, as well as a great variety of plants.

The area had been populated by tea tree and indigenous grasses. There were also forest trees, including She oak, Manna Gum and River Red Gum.

Trees were used by Traditional Owners for a range of purposes such as making weapons, tools and implements, and canoes.

The boughs, bark and leaves of different trees were utilised for different purposes. A light tree cover was probably maintained through firing the ground seasonally, which stimulated new growth of pasture for grazing animals such as kangaroos and wallabies, as well as herbs and tubers.

A place to meet

The central Melbourne area was a long-established meeting place of the five language groups of the Kulin nation—Woi-wurrung, Boonwurrung, Dja Dja Wurrung, Taungurung and Wathaurung.

During these meetings (which usually took place in the warmer months when food resources were plentiful), Traditional Owners conducted ceremonies, traded goods, organised marriages and resolved disputes.

Like other areas of high ground in the vicinity of the lower Yarra, on both the north and south banks, the area around the Domain was a place to gather and camp. Being high ground, this area had strategic advantages and offered views of Birrarung and of Nerrm beyond.

The Domain was a Kulin burial ground, as ancestral remains were uncovered there in 1929 when the foundations of the Shrine of Remembrance were dug.

William Thomas, Assistant Protector of Aborigines for the Western Port District, noted that “splendid swamps by the Yarra” were favoured fishing spots for local Traditional Owners and regular meeting places for clans.

According to William Thomas, the Bunurong held meetings every three months, and corroborees on occasions of full and new moons.

Message sticks and smoke signals were used for communicating with neighbours, with high points in the area, such as Emerald Hill (present-day South Melbourne), St Kilda Hill and Point Ormond, being ideal lookouts for such signals.

Emerald Hill, in particular, was known as a traditional social and ceremonial meeting place for Traditional Owners, with reports in 1840 describing 50 men dancing to musical accompaniment in the area.

The impacts of early colonisation

The Kulin faced the invasion of their Country that began in the early 19th Century, initially by sealers and colonists from Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), who were seeking to expand their pastoral opportunities across Bass Strait.

Although they had no authority to settle at Port Phillip, which was at that time outside the limits of settlement, the British Home Office and the colonial authorities in Sydney were pushed to approve the new settlement at Port Phillip in 1836.

The first permanent Europeans to live in Melbourne, led by John Batman (representing the Port Phillip Association) and John Pascoe Fawkner, arrived in present-day Melbourne and took up land in mid-1835.

When Batman arrived, he referred to the place as Doutigalla, which he incorrectly believed to be the Traditional Owner name for the place.

Batman claimed to have made a ‘treaty’ with the Traditional Owner ‘Chiefs’ in June 1835 that entitled the Port Phillip Association to 600,000 acres of land in exchange for various trifling items of European manufacture and a yearly tribute.

The ‘treaty’ was subsequently declared invalid by the British Home Office and the Governor of New South Wales, Richard Bourke.

The New South Wales Government claimed that the Port Phillip District (Victoria), as part of the Colony of New South Wales, had been taken possession of in the name of King George III in 1788.

The British colonial authorities failed to recognise the sovereign rights of Traditional Owners to their Country.

The Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate

In the years that followed, Traditional Owners faced devastating impacts of colonisation to their land and people.

From the 1800s, sealers working in Bass Strait kidnapped Bunurong women and children from the Victorian coast and took them to the Bass Strait islands. Those abducted included the wives of distinguished Bunurong men, including Derrimut.

The colonial government assumed ownership of the land and its waterways and denied Traditional Owners free access to and occupation of their Country, an inheritance many tens of thousands of years old.

The government surveyed the land in Melbourne, dividing it into parishes and allotments, and set about selling sections of this land to the public.

As more Europeans arrived in Melbourne, more land was sold off and the amount of public land, or Crown land, that was available for Traditional Owners to access grew smaller.

In 1838, the Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate was established in an effort to protect Traditional Owners from the dangers posed by European settlers. Local Traditional Owner men also joined the Native Police Corps, which was also established in 1838.

An Anglican Mission for the Traditional Owners in the Melbourne area was established on the south bank of the Yarra, on a site that later became the Melbourne Botanic Gardens. This operated from 1837 until 1839 and included a mission school for Traditional Owner children.

Cultural practices despite displacement

At the time that Europeans arrived and took up this land from Traditional Owners, Traditional Owners were living in clans (large family groups), which collectively made up a large and complex society.

Europeans recorded their observations of Traditional Owners life and interactions with Traditional Owners in the Melbourne area during this period, including accounts of corroborees and the areas of Melbourne where Traditional Owners set up their camps.

Within a complex of camps on the south side of the river (in the vicinity of today’s Domain and Botanic Gardens), Traditional Owners continued many of their cultural practices, but under enormous constraints and significant duress.

Despite the profound dislocation caused by the invasion of their Country and the extensive losses and suffering involved, Traditional Owners endeavoured to find a way to survive.

In the late 1850s, many of the Wurundjeri people remaining in Melbourne had been moved to Acheron Aboriginal Reserve and then in 1863 to Coranderrk Aboriginal Reserve.

The Bunurong had been provided with a ‘camping reserve’ at Mordialloc in 1841, but there were few people remaining there by the late 1860s.

Detrimental health impacts

As colonisation progressed, the Traditional Owners’ Country was taken away from them, in the name of the British colonial government, along with access to water and other necessary resources.

A combination of factors also contributed to high mortality rates among the Traditional Owners living in Melbourne in the 1830s and 1840s. These factors included the impact of fatal European diseases, such as syphilis and influenza, for which they received poor medical treatment; exposure to alcohol and violence against Traditional Owners by European settlers, much of which went unreported. Underpinning the experience of invasion and dispossession were the compound psychological effects of deprivation and trauma, and profound grief, despair, and desolation.

Traditional Owner women’s physical and mental health was compromised by the cataclysmic change to Traditional Owner society in this period, which was detrimental to the Traditional Owner birth rate.

The Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate was abandoned in 1848, leaving Traditional Owners without land and resources and in an increasingly vulnerable situation.

Despite the closure of many of the missions and reserves in the decades that followed, the lives of Traditional Owners continued to be disrupted and heavily controlled by the government policies.

One harrowing example was the belief from church and welfare groups that Traditional Owner children would be better in foster care and institutions, which resulted in many Traditional Owner children being taken away from their families. This caused enormous damage to Traditional Owners and continues to cause great suffering today.

Yannawatpanhanna: go to water

During colonisation, the Bunurong would make regular trips from Mordialloc to Melbourne, where they camped at the Albert Park lagoon, and also in the Domain and Fawkner Park.

The lagoon at Albert Park continued to provide valuable food resources for Traditional Owners in the early settlement period, including yabbies, eels, birds and plants. Plant resources would have included swamp herbs (carrum).

The Wurundjeri and the Bunurong also continued to source food on the foreshore of Nerrm, including fish, mussels and other shellfish.

The water, both from the Albert Park lagoon and the foreshore along Port Phillip Bay, was an enduring source of nourishment and sense of Country.

To recognise this enduring history and the continuous living culture of Traditional Owners, the Shrine to Sea project will plan for ways to bring Aboriginal language and knowledge back onto Country. As a first step, an agreement has been reached between DEECA and Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation on renaming of the Shrine to Sea boulevard to reflect its First Nations origins.

‘Yannawatpanhanna’ (Yan-uh-wot-pan-han-uh) means “go to water” in the Boonwurrung language, and has been selected as an ideal fit for the boulevard, which concludes at the Kerferd Road Pier. This name will now form the identity and visual branding of the interpretation and signage created as part of ‘Celebrating Local Stories’.

For more information on the renaming of the project, go to the March Update on the Shrine to Sea webpage.

This is the final instalment of the Celebrating Local Stories series. Browse Part 1 - 4 in the series here.

Page last updated: 28/03/23